Virtual Field Trip

from virtual-geology.info

Locality 1.3 Chimiche

It is important that you access

this field trip on a laptop or desktop PC.

Click on any image to enlarge

it - you will need to zoom in to see sufficient detail.

Where are we? We will study

a section in disused quarries along road TF-28, about 600m north of the village

of Chimiche, between km posts 66 and 67. The lower part of the section is exposed

south of the road, and the upper part is in the quarry north of the road. Take

a good look around the area in Google

Maps and Streetview.

There's a lot to see and do at this location, and we usually spend 2-3 hours

here.

Stratigraphy: most of the

section exposed here belongs to the Granadilla Formation, which is part of the

Bandas del Sur Group of Pleistocene age. The age of the Granadilla Formation

has been determined at 600 ± 9 ka (i.e. 600,000 ± 9000

years), dated by 40Ar/39Ar analyses of sanidine crystals

(Brown et al., 2003). The rocks seen here are all phonolitic in composition.

|

Figure 1.

General view of the whole section. In the foreground is the quarry south

of the road. Behind the large pine tree can be seen the quarry on the

north side of the road. The road is hidden from view: it is roughly at

the level of the person seated below the tree.

|

| |

Figure 2.

View of the upper part of the section in the quarry on the north side of

the road. |

Economic geology: let's think

briefly about why there are quarries here. Two types of material have been quarried:

poorly consolidated pumice from the lower (south) part of the section (we'll

call it Unit G1), and the compact, massive rock (Unit G3) in the quarry north

of the road.

|

Figure 3.

Artificial caves carved into lightly consolidated pumice of Unit G1. These

caves were probably used for agricultural storage. Blocks from Unit G3

are piled on top of the outcrop.

|

Figure 4.

The pumice from Unit G1 is often used as a thick mulch for growing crops,

to conserve moisture in the semi-arid climate. Here, potato fields have

been mulched with pumice; grape vines grow around the edges of the fields.

|

Figure 5.

View of extensive quarries in Unit G3, south of the studied section. The

rock is easily sawed into lightweight blocks used for construction - effectively

these are natural breeze blocks. |

|

Figure 6a.

Wall built of cut blocks of Unit G3.

|

Figure 6b.

The entrance to the town of Granadilla; the plinth is made of blocks cut

from Unit G3.

|

Figure 7.

Aqueduct for crop irrigation, made of carved blocks of Unit G3. A plastic

pipe has been added later to reduce water loss through seepage and evaporation. |

Question: what are some other economic uses of pumice, from Tenerife or

elsewhere?

Question: what are some other economic uses of pumice, from Tenerife or

elsewhere?

Tasks

At this location, we will make a

detailed log of the Granadilla Formation.

- Your goal is to measure and describe

the section and to produce a graphic log of it, just as if you were in the

field.

- The photos are your outcrops,

and you'll need to spend time studying them in detail, and working out the

relationships between them.

- Pay particular attention to field

relationships - contacts between units, how units change as you trace them

laterally, etc. Look particularly for evidence of time gaps in the section.

- Make sure that you also answer

questions in the text or associated with individual images.

Logging

instructions. Log paper (pdf;

PowerPoint; odp)

Logging the section

We have divided the section up into

lettered units to get you off to a good start.

For each unit, record:

- the nature of its basal contact;

- its thickness, and any lateral

variation in thickness and overall geometry;

- distinctive features such as colour

or the way it weathers or forms landscape features;

- its lithology, in detail, using

the appropriate hand specimen description scheme for either crystalline or

fragmental rocks; give the rocks names, for example using the volcaniclastic

classification scheme;

- any changes in lithology (e.g.

is there a concentration of clasts or vesicles in any particular part of the

unit?); record changes both vertically through the unit, and when you trace

the unit laterally;

- internal structures such as bedding

or flow banding;

- from your observations, you should

be able to attempt interpretations of the processes and conditions involved

in the formation of each unit in the section, and include those interpretations

on your log. You should then attempt an overall interpretation of what the

section represents.

The section south of the road:

Unit G1

Figure 8.

The quarry face, showing Units G1, G2 and G3. A indicates the top of the

underlying Abades Formation, exposed in the quarry floor.

|

Figure 9.

Close-up of point A in Figure 8. The brown paleosol at the top of the

Abades Formation is overlain by pumice at the base of Unit G1 of the Granadilla

Formation. What is the significance of the paleosol?

|

Figure 10.

The quarry face. Obtain a thickness for Unit G1. Assume that there is 50

cm of G1 in the quarry floor, from the base of G1 (Figure 9) to the foot

of the face, and that the tallest geologist (centre of the group of 3) is

1.8 metres tall. |

Figure 11.

Measuring a section through Unit G1. Study this part of the section in detail

in Figures 10 and 11. Can you see any structures or variations within G1?

If so, describe them, and show that information graphically on your log. |

Figure 12.

Close-up of the phonolitic pumice of Unit G1. The pen is 15 cm long. Describe

this in detail, using the hand specimen description scheme. Make sure you

include features such as grain size, sorting and grain shape. |

Figure 13.

Zoomed-in view of Figure 12. How much matrix (ash, < 2 mm) can you

see between the pumice clasts? This observation will affect your estimate

of sorting, and your interpretation of processes.

|

Figure 14.

Hand specimens of pumice clasts from Unit G1. Describe features such as

vesicle percentage, size and shape. |

|

Unit G2

Don't forget to zoom in to see and

record the detail in these outcrops.

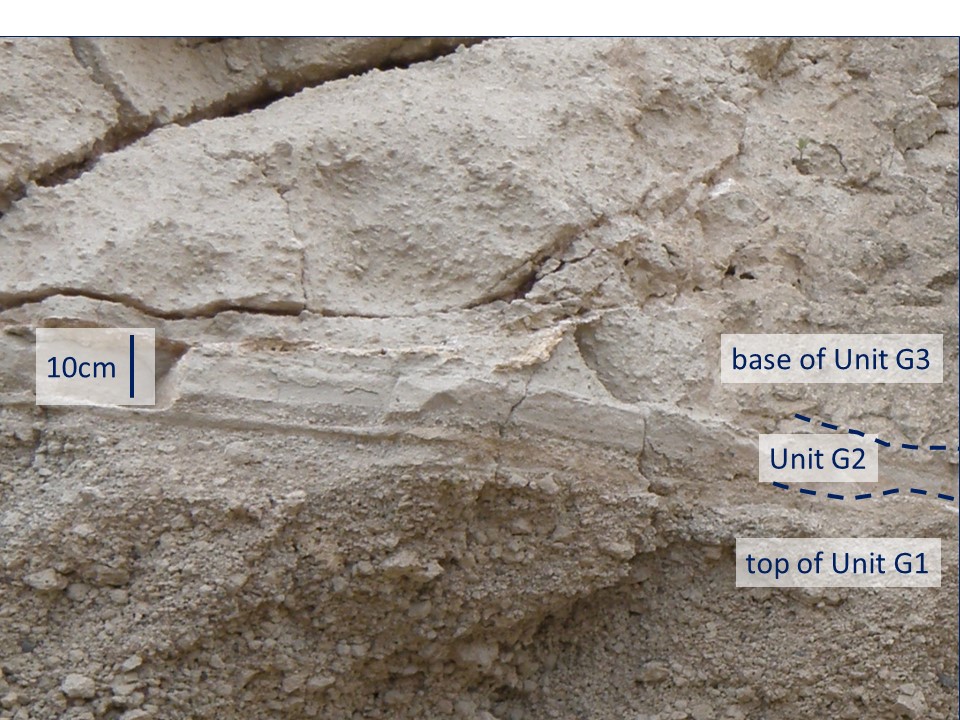

Figure 15.

The upper part of G1, the thin Unit G2 (arrow) and the lower part of G3. |

Figure 16.

The same sequence exposed in the road cut. Unit G2 is at shoulder level

of the person on the left.

|

Figure 17.

Another view of the road cut showing the top of G1, G2 and the base of G3

beneath the large pine tree - the endemic Pinus canariensis. |

Figure 18.

From another location. This is a detailed view of Unit G2, showing its

internal structure.

Using Figures 15 - 18, describe

all the visible characteristics of Unit G2.

|

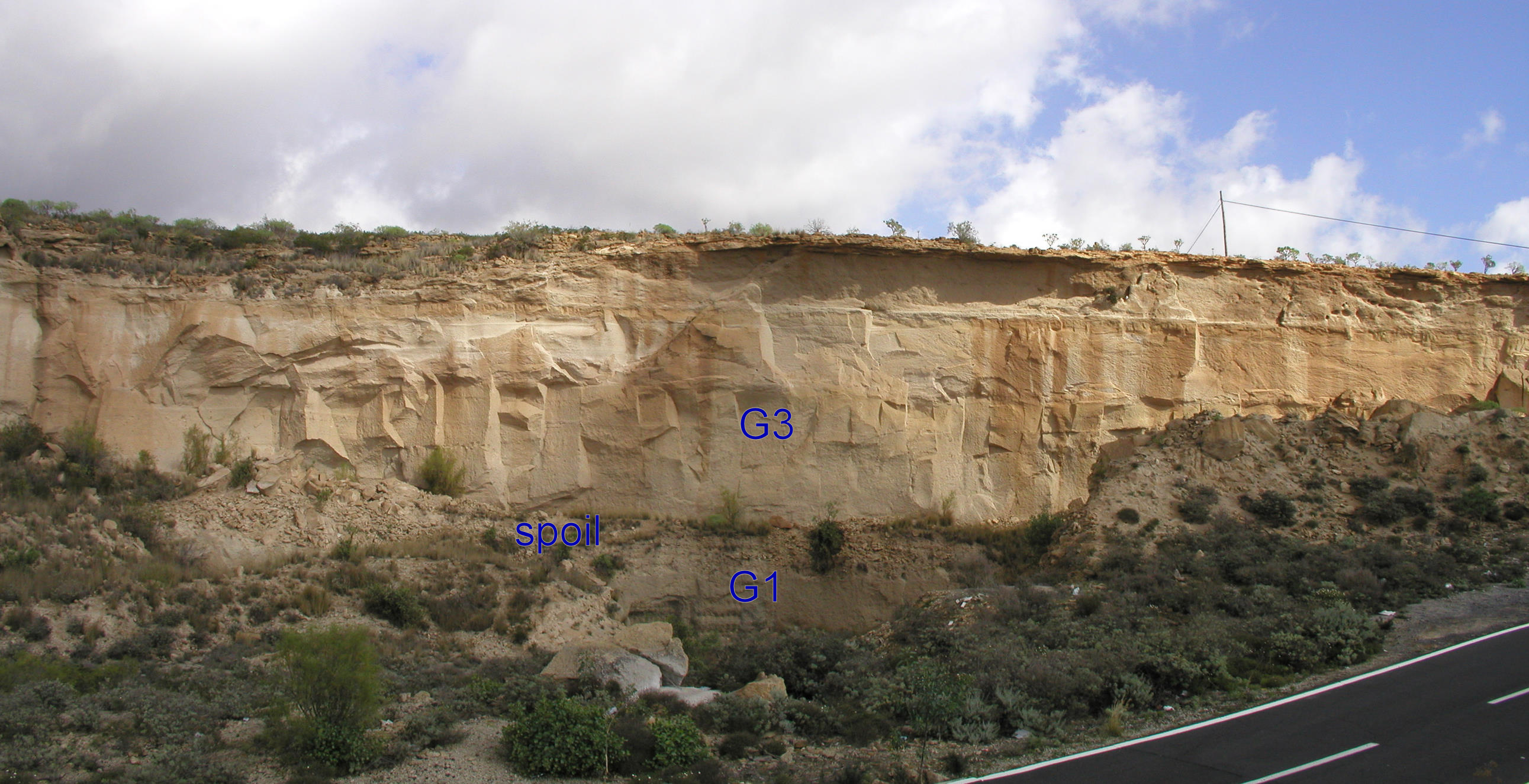

Unit G3

Figure 19.

A general view of the quarry north of the road. G1 is exposed in the lower

part of the quarry. G2 and its lower and upper contacts are obscured beneath

spoil (quarry waste). |

Figure 20.

Estimate the thickness of Unit G3. Assumptions: the geologists in the centre

of the photo are 1.7 m tall; the base of G3 is approximately at the position

of their feet; at the top, G3 is overlain by Unit H, which is a darker orange

colour. |

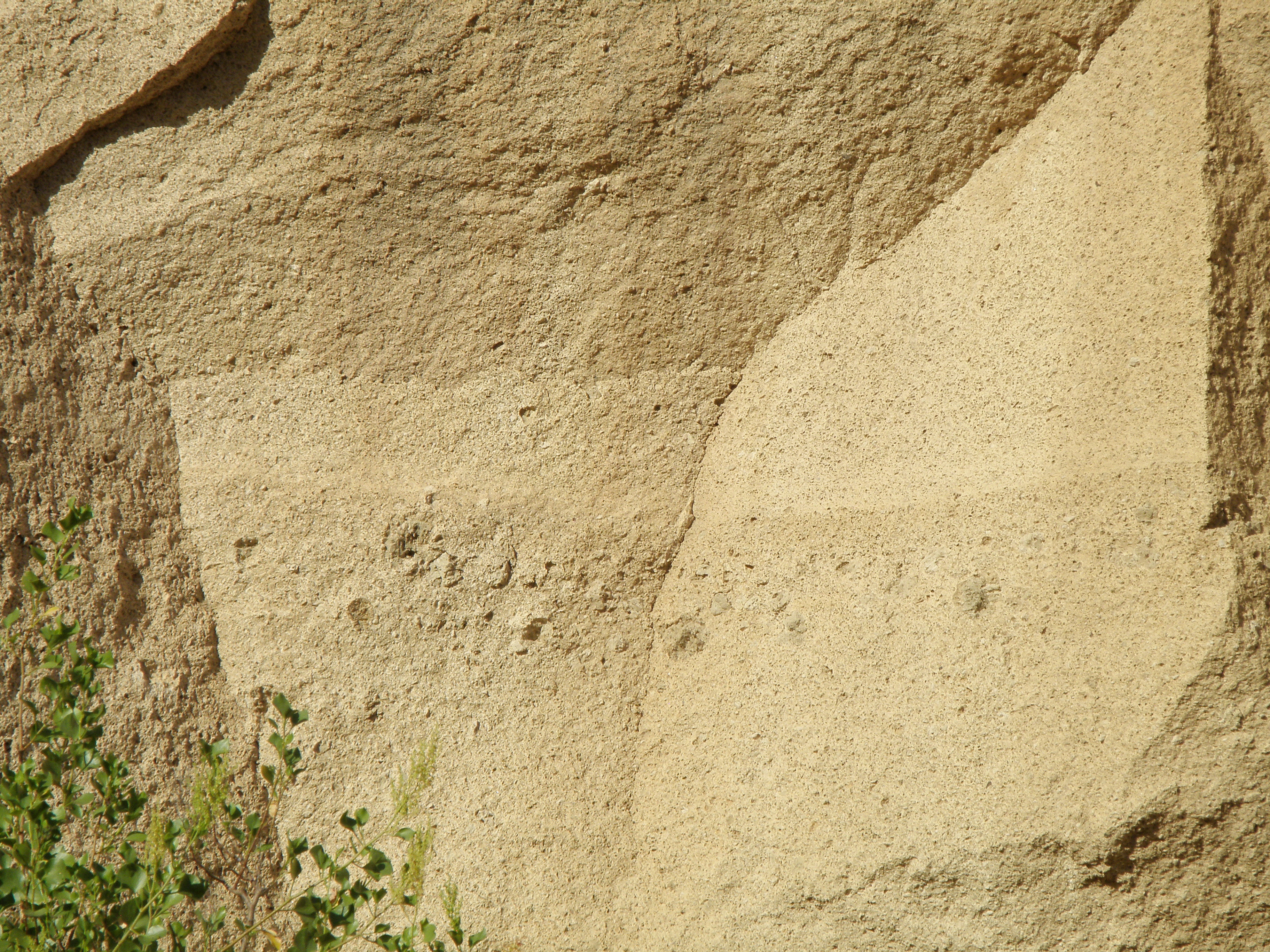

Figure 21.

Closer view of the quarry face in Figure 20. Zoom in and describe all the

features you can see in Unit G3 in this view and in Figure 21. |

Figure 22.

Close-up of Figure 21. |

Figure 23.

The quarry face through most of Unit G3. Its base lies below the photograph.

At the top, the overlying thin Unit H is darker and partly overhanging.

Is G3 a single, massive unit, or can you see any features or changes within

it? |

Figure 24.

Close-up of Figure 24. Zoom in to see the detail. Do you think you can

subdivide Unit G3? If so, you could show this on your log, using sub-units

such as G3a, G3b etc., and describe differences between sub-units. Scale:

the geologist standing to the right of the tree is 1.9 m tall.

|

Figure 25.

Detail of the lower part of the quarry face. The thin light band is also

seen in Figure 23, at head level of the 3 people behind the bush. |

Figure 26.

Further detail of the lower part of the face. |

Unit G3 in close-up

The top of the section

Above Unit G3 is a very different

looking, bedded sequence: let's call it Unit H, although it can undoubtedly

be subdivided.

Figure 35.

Image by Adrian Watson |

Figure 36.

Close-up of part of Figure 35. Look carefully. Where exactly would you place

the base of Unit H? Is it planar or irregular? Is there evidence of erosion

at the base?

Note the darker brown unit, seen also in Figure 37. What might it represent? |

Figure 37.

Detail of the top of G3, overlain by H. Describe the characteristics of

the various beds in H. Try to interpret this unit in terms of processes.

|

|

*** At this location, the contacts

between the units are all sub-horizontal. Let's take a side trip to contrasting

sections further west which will give us some vital additional information.

Interpreting the field evidence

You have now acquired a variety of

different types of data to be represented graphically on your log.

Logging instructions (pdf). This includes lithology, sedimentary structures

and field relationships. Once your log is drawn, your task is to interpret the

data.

- Subdivide the log into numbered

units from A (base not seen) through G1, G2 and G3 to H (top not seen).

- For each numbered unit or significant

surface on the log, write a brief interpretation of the processes and conditions

of formation in the right-hand column of the log. Include in your interpretation

information such as volcanic or sedimentary processes and their energy. There

must be evidence to support all of your interpretations.

- Write a short (250 word maximum)

interpretative account of changes in processes, conditions and environments

from the base to the top of the logged sequence, indicating where there may

be substantial time gaps. How long did it take to emplace the sequence from

G1 to G3? Where is its source?

Just for fun...

Image: Abhay Kumar via

Wikimedia

Commons |

Canarian potatoes are famous

and delicious, and you'll find them on just about every restaurant menu

in Tenerife. The potatoes are grown in small, terraced fields all over

the island, and the fields are often mulched with pumice

to conserve moisture. Traditionally, the small new potatoes are boiled

whole in sea water until dry, leaving a thin salt crust. These papas

arrugadas ('wrinkly potatoes') are then served with traditional sauces

- a red chili sauce (mojo picón) and a green coriander sauce

(mojo verde).

Recipes

|

Next locality

Make sure you've completed all the

work for this locality. Now we can get back on the virtual coach and head off

to our next stop.

Field trip home page

Field trip home page

This page is maintained

by Roger Suthren. Last updated

8 March, 2021 2:36 PM

. All images © Roger Suthren unless otherwise stated. Images may be re-used

for non-commercial purposes.

![]()

![]() Question: what are some other economic uses of pumice, from Tenerife or

elsewhere?

Question: what are some other economic uses of pumice, from Tenerife or

elsewhere?![]()

![]()

![]()