| home | virtual field trips | regional geology | images | e-learning | links |

The texture of a rock is the relationships between the components of the rock - how they are arranged.

Grain size is described according to the Wentworth scale, where terms such as fine sand or cobble have a very specific meaning. Use a grain size comparator for accuracy in the laboratory and in the field. It is also important that you know the width of the field of view of your microscope at each magnification (measure it, if you don't know) to estimate grain size.

|

Wentworth scale for the description of grain size of sediments: click to enlarge |

|

Grain size comparator: click to enlarge |

Sorting describes the range of grain size. Samples in which most of the grains fall into one size class on the Wentworth scale are well sorted. We can illustrate sorting by plotting the grain-size distribution of our sample.

Textural maturity of a sediment [scroll down to Sediment Maturity]

|

Boggs, 1995, pp. 79-93: Grain size & sorting; phi scale (p. 80) Tucker, 1991, pp. |

|

|

Note: all references to Boggs, 1995 and Tucker, 1991 in these pages refer to: BOGGS, S. 1995. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy (2nd edition). Prentice Hall. TUCKER, M.E. 1991. Sedimentary Petrology (2nd edition). Blackwell. |

Grain shape can be described in terms of:

|

Boggs, 1995, pp. 94-102: Grain shape Tucker, 1991, pp. 15-16 |

Sedimentary rocks may be either grain-supported or matrix supported. This applies equally to sandstones, and to coarser rocks such as conglomerates and breccias.

|

Grain-supported (or clast-supported) conglomerate, with a sandstone matrix. All of the pebbles are in contact in 3 dimensions, forming a framework. |

|

Section cut through a grain-supported conglomerate with a silica cement. All the pebbles are in contact in 3 dimensions, but in most cases the actual contact is not seen here - it occurs above or below the plane of the section. When the grains appear as close together as this, it is almost certain that the rock is grain-supported. Beware of the apparent lack of grain support in sandstone thin sections where the grains are close together. |

|

A matrix-supported breccia. Here, the small, angular pebbles are separated by several pebble diameters. Most of the rock is composed of mud-sized matrix, in which the pebbles 'float'. |

In thin section, it is important to remember that we are seeing a 2-dimensional section through a 3-dimensional rock - not all the grain contacts may be seen, and we may get a false impression of grain size and sorting:

|

This artificial 'sediment' consists of wooden spheres, embedded in clear

resin. In this 3-D view, we can see that the spheres are of uniform size,

and are in contact with their neighbours (point or tangential

contacts). Packing approximates to cubic close packing.

Model by Richard D'Lemos |

|

These are cuts through the same 'sediment'. On the cut surface, note that:

|

|

Beware of the problems of studying a thin section which may give a distorted

impression of the rock texture:

|

|

Boggs, 1995, pp. 94-102: Grain shape Tucker, 1991, pp. 15-16 |

|

Boggs, 1995, p. 107: Grain contacts Tucker, 1991, p 18 |

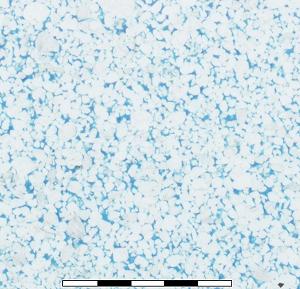

Porosity is an aspect of texture which is of particular interest to the economic geologist, because it is in the pore spaces that economically valuable fluids such as oil, gas or water may be contained.

Primary porosity is formed at or before the time of deposition: it occurs between and within the grains.

Secondary porosity is formed during diagenesis, usually by solution/dissolution of components of the rock.

Both primary and secondary porosity are progressively destroyed as sediments are buried, mainly by processes of compaction and cementation.

This page was written by Roger Suthren

![]()

This page is maintained by Roger Suthren. Last updated 22 November, 2021 12:16 PM